Imprint 2021/5

FÓRUM TÁRSADALOMTUDOMÁNYI SZEMLE

FORUM SOCIAL SCIENCES REVIEW

ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE

Volume XXIII (2021)

Head of the Editorial Board: LÁSZLÓ ÖLLÖS

Members of the Editorial Board

Zoltán Biró A. (Romania), Csilla Fedinec (Hungary), Holger Fischer (Germany),

László Gyurgyík (Slovakia), Péter Hunčík (Slovakia), Petteri Laihonen (Finland), Zsuzsanna Lampl (Slovakia), István Lanstyák (Slovakia), Zsolt Lengyel (Germany), József Liszka (Slovakia), András Mészáros (Slovakia), Attila Simon (Slovakia), László Szarka (Hungary), Andrej Tóth (Czech Republic), László Végh (Slovakia)

Content

Studies

ÖLLÖS, LÁSZLÓ: Hungarian–Slovak Reconciliation and the National Peace

GYURGYÍK, LÁSZLÓ: The Ethnic Composition of Slovakia’s Municipalities, Based on the Data of the 1950 census

LAMPL, ZSUZSANNA: The Primary Results of the last Hungarian Identity Survey in Slovakia

LANSTYÁK, ISTVÁN: Language Problems, Language Related Social Problems, Metalinguistic Activities

SIMON, ATTILA: The Banned, the Controlled, the Shifted, and the Compulsory. National Holidays and the Hungarians in Slovakia in 1919

TÓTH, ÁGNES: In the Margins of a Party Resolution. The 1968 Resolution of the Political Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’

Party on the Situation of the Nationalities in Hungary

Central European Forum

EVERETT, JUDAS: Combatting Illiberalism in the Heart of Europe: Lessons from Slovakia

Reviews

Öllös, László: European Identity

(András A.Gergely)

Lampl, Zsuzsanna: The political identity of ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia, 1989-1990

(Gábor Csanda)

Gecse, Annabella: The Heart of Gemer/Gömör. Studies on the popular religious practice of Gemer/Gömör in Southern Slovakia

(Péter Vataščin)

Liszka, József (ed.): Acta Ethnologica Danubiana 22. – Az Etnológiai Központ Évkönyve – Ročenka Výskumného centra európskej etnológie – Jahrbuch des Forschungszentrums für Europäische Ethnologie

(Katalin Pajor)

Guidelines for Authors

Authors

Hungarian–Slovak Reconciliation and the National Peace

For three centuries, Europe has been organized into nation-states. This situation did not even change after the European Union had been established. The European Union, despite having its own central decision-making and executive bodies, is under the influence of its most powerful member states. The governments of these states decide over the main questions of the Union. The smaller member states could have significant influence only if they organize themselves in interest-groups, mainly on a regional basis. Together they could become strong enough to outweigh the power of the larger states, but still only in some issues. To achieve more, they need to build up a broader alliance of different state-groups.

It is a situation when nation-states fight each other, without a war, of course. But the main aim of the interstate relations remains the same. Their form is milder, but substantially unchanged. That is, the relations are based on strength and power regulated by national interest. (Horowitz 1985: 4)

Creating a commonly accepted system of values in political decision-making on a higher level could be realized by supporting the main components of a modern political society. But it needs reconciliation between nations.

The reconciliation between the small nations of Central Europe must be determined by basic national issues. The democratization of these countries and their independence depend on it. More than three decades after the revolutionary wave that triggered the change of regime, several small nations, including Slovaks and the Hungarians, still continue to fight against each other on a national basis. Their diplomatic efforts, many elements of their countries´ internal legal systems, their political parties, and the programs of many of their organizations are aimed at national victory over one another. When acting against each other, neither their accession to the European Union, nor their membership in NATO prevents their governments from orienting themselves toward great powers. As part of their strategy against their neighbour, they offer themselves to the supporting great power as a zone of influence. This, as they believe, strengthens their position in the European Union.

The issue of the Hungarian–Slovak reconciliation is one of the most important ones in regard to the future of the region. Both reconciliation and the absence of it, have had and will have a significant impact on the political community in both countries. It also sets an example, one way or another, for neighbouring countries. At the same time, as a non-negligible element of the experiment called EU, it can further or even hinder the solution of one of the fundamental problems of the Union, the conflict between the nation-state and the effectiveness of continental decision-making.

Reconciliation and the Visegrad Countries

By abandoning to serve a great power, small Central European nations renounce their sovereignty too. Their national advancement could only be expected from the service of one of the great powers. But for serving a great power, they should also adopt its poli tical system and serve its interests, oppressing and sometimes destroying others. (Kučera 2008: 39)

The national liberation of one party is linked to the national subjugation of the other. The extension of national freedom of one nation does not mean its further extension to another. Instead, it means a new dominance. National freedom also means national slavery. Not only did this model reinforce, but even made dominant the belief that the national freedom of one nation does not strengthen but it even endangers the freedom of the other.

It seems that whatever can be done with the support of great powers: even territories can be acquired, and the population of other nationalities can be expelled from those territories. Great powers never require effectively enough that national freedom and equality of nationalities is guaranteed.

The rejection or absence of the universal principle of national freedom and equality gave way to total national relativism. The principal here is that the human rights of other national minorities can be violated and their collective national life can also be obstructed or even prohibited. The national development of one nation is linked here to the national oppression of the other. One party links its own national future (i.e. persistence, survival) to the destruction and oppression of the other party.

This has a significant impact on the political culture of the two countries and, of course, on the behaviour of the majority of their leaders to this day.

Today’s interest alliance of Visegrad for reconciliation is worth little. The interests are temporary. Of course, it is difficult for the parties to expect more. There is the experience of past centuries of attempts to nationally destroy each other. And because of this experience, they have demonstrated to their own public how the other side has tried to do so. Therefore, now they have to listen to their own public which has been socialised in the spirit that the other side had tried to destroy them as a nation. Part of their current experience is that they only communicate their own threats to their own public. From this they conclude that the other side is communicating the same to their own public, in relation to themselves.

Their cooperation today is nothing more than a connection of interests. They are aware of its relativity. They are willing to cooperate with each other only to the extent that it does not change the essence of their national values established by the end of the twentieth century. This cooperation is subject from time to time to the disruptive intentions of external forces, considering the fact that the parties have repeatedly confronted, and even betrayed, each other whenever they expected a national gain. And this national gain came from one of the great powers that wanted to dominate the whole region in general. So, both the one that is currently supported and the one that is shortened.

The small state puts its foreign policy strategy of variable alignment with the great powers ahead of stable, reliable federal ties. From the point of view of small states, national security can only be ensured with the support of a great power, not even with any of them, but with the victorious one at any given time. Therefore, a rapid transition from one power to another is considered one of the fundamental requirements of their national security. They must therefore pursue a foreign policy so that the transition remains possible. This is called a balanced foreign policy. For if the neighbour becomes faster, he will be rewarded by the great power that is just becoming dominant, and following Niccolo Machiavelli’s admonition, he will not do it on his own.

It follows logically from the essentially threatening hostile relationship with a neighbour to serve the power that is becoming dominant at any given time. To them, only the full unification of small nations and the joint rebuilding of their position of great power would offer a real alternative. But there are high cultural barriers to this decision. There is some hope that these barriers, raised by them themselves, can also be torn down by them. But they have made it part of their national identity and are imbued with it so much that today they are even afraid of faltering. Therefore, a new idea must be offered.

The Ethics of Ambiguity

Ambiguity has become a moral category. It is something that needs to be protected. The moral essence of ambiguity is that the claim that certain elements of backwardness are more valuable than the state of development. For this, of course, this development must be seen as a vestibule of decay and fall, and if the fall does not occur, there must be no doubt as to the future realization of the prophecy. And, since all (highly) developed cultures will once undergo a crisis, how can anyone now claim that they could not get into trouble someday? What is really needed, however, is the way you could get to the forefront of development again. This is because criticism of the more advanced is not accompanied by a real development strategy that shows a different path. Rather, it attempts to mobilize only with predictive visions, and detailed programs that are feasible and measurable in their effectiveness are not born.

The ideological protection of backwardness is linked to the protection of those who cause backwardness. If they did not cause backwardness but prevented other people from embarking on the path of decay, then morally noble deeds could be associated with them. Thus, they retain their moral right to retain or regain power. The uncontrollability of the claim requires a vision and a passionate political identity. Strong passions instead of rationality, and attachments to them, that are powerfully held in power. Passions are primarily national passions. They rest in the constant strengthening of the temperaments of the offended national self-consciousness. The goal is not to resolve the offense, but to increase the pain, to strengthen the sense of pride of the offended.

However, the essence of Central European ambiguity also includes relative separation from the East. In contrast to the Eastern empires, they see themselves as Western, and therefore more developed. In spite of many features of their culture, including their Eastern political cultures (Bergyajev 1989: 200-201), they did not consider themselves to be part of the East. Otherwise, they should have accepted the na turalness and correctness of their repeated conquest by the East. Although some of their political elites spread this ideology, they knew their society did not want to become either Turkish or Russian, and they did not want to merge into these empires either. And with few exceptions, they themselves did not want to do so, even if they supported the rule of these empires and spread many elements of their culture with their power from their conquering lords.

However, masters of ambiguous separation still face another challenge. They also need to divide their societies, separate them from each other. Towards their eastern conquerors (Figes 2002: 368-371) they have behaved as more eastern, that is, more communist, more pro-Russian. When they were conquered by a western power (Simms 2013: 219), e.g. the National Socialist Germany, they presented themselves as more German-friendly than their neighbours. And more Western when they joined the democratic West, while at the same time pushing back their neighbours. And when they approach East and West at the same time, they will argue in two ways simultaneously.

Moreover, even in several ways, as the Central European country sometimes wants to adapt to more than one great power. It is not the resolution of the contradiction but its maintenance that becomes a political and cultural goal.

If a Central European country is positioned in more than one direction, it is not duplicating, but pursuing its own interests. It doesn’t necessarily perceive it as a dichotomy, tending here and tending there. If I am better positioned, if I jump to the other side at the right time, then I am at an advantage and he is at a disadvantage.

In other words, the power, the economic, and cultural consequences of duplicity should be accounted for. That is, the main consequence of power is not the independence of the region, but its suspension on the pretext of national fight with each other. (Smith 2004: 154) The formerly unified economic space is being dismantled, creating small units that are operational by depending on the currently dominant power. They did this in the twentieth century, in an age when the national markets that had been considered big have turned out to be small.

In the age of colonized markets, breaking down former big market units into small ones means that the dependence of the small ones on the big ones is growing. But it is also culturally necessary to separate those who were previously closely related. This is based on linguistic separation. They try to achieve it by creating linguistic dominance. The education system forces only the minority to learn the language of the majority, but it does not require the majority to learn the minority language. Not even in settlements or regions where they live together. The other language becomes an instrument of oppression as the two languages are not equal. With the break-down of Austria-Hungary, the dominance of the Hungarian language is not replaced by linguistic equality, but by the dominance of the Slovak one. This eliminates the ability of the members of the majority to form a picture of their neighbour’s culture, public life and the positions of their politicians.

Another important element of cultural separation is enemy construction. (Glover 1997: 11) The other side’s past is set in such a way that, for its own nationalists, only national fight seems like a viable path. And this would be difficult to achieve without linguistic division. If the majority understood the language of the minority, they could learn about the events of their common past that has benefited them all. But the injustices and inhumanities committed by their own people could not be concealed or, they would be much more difficult to misinterpret. They could get acquainted directly with the current views, positions, proposals and initiatives of the other nationalists without domestic interpretation and without misinterpretation. (Clark 2013: 558-561)

This is because their public opinions would converge, partly forming a common public opinion. Thus, arousing and manipulating national public opinion would become much more difficult, and, subsequently, the opportunities for the élite of the national minority to militarize that minority’s public opinion would also be limited.

Another important consequence would be the convergence of public opinions. A much denser web of direct relations between members of nations can be woven, especially in case of their cultural separation based on enemy construction. (Hirschi 2012: 214-215) And it could not merely be interest-based economic relations, but a full range of human relations.

It was not regional multiculturalism but segregation from what was declared a national enemy that became an example to follow. If someone, as a Slovak, publicly states that he/she speaks Hungarian and knows Hungarian culture, he/she becomes nationally suspicious, and therefore less valuable. In the value system of national struggle, someone who loves, and even someone who can only love the enemy, ranks lower in the value scale of fight as they become suspicious. Anyone loyal to their nation does not speak the other language, even if they could, but forces the other one to use their own language. It does not articulate the values of the other culture, but points to how much more valuable one’s own culture is.

If they can assert their own respective interests, mutual assistance will become the expected norm (of behaviour). They do not hold themselves responsible for the fate of the other party, if only in the sense that they do not fight them. In the case of a relationship of interest, alliances are formed within the boundaries of interests. But relationships whose publicly voiced essence would be responsibility for the other are not born. Yet it is quite clear that their decisions have a significant, and sometimes decisive, influence on the present and future of their national neighbours.

Making the shift away from responsibility a social value is becoming the main reason for the lack of solidarity within the European Union. Accession to the Union is also perceived mainly as an advocacy by the country’s political leadership as well as by a large part of society. Many are not even able to see the issue differently. And others were interested in not even being able to. Their argument is: making national advocacy a supreme value makes universal values volatile. The state of the fight and of potential combat makes awareness of the threat one of the main aims of politics. The other party is both a current threat and a potential threat.

Characterization of the other party is not possible otherwise. The desire to fight is all an unchangeable gift. Such is the essence of humans.

The consequences for ourselves: why we have to be all our supposed enemies and how we can become like that. They can be used to justify the violation of universal human values by invoking national goals. And local characteristics can be used to explain the national characteristics of neighbours in such a way that they appear invariably hostile.

With this hostility they give up their real sovereignty. In the age of global cultural competition, they also have weaker cultural chances because of the national cultural separation.

The Essence of Reconciliation

What does the state of peace between people mean? The essence of reconciliation in the age of modern mass politics lies in the desire of the people for peace. (Kant 1998: 315-318) Above all, they have a strong intention to end the war. But that intention alone could be a ceasefire. The foundation of peace is more than that: peace comes not only from the cessation of war (Macmillan 2002: 499-500), but from the intention to coo perate. And from the realization that cooperation is more noble and useful than fight.

Just as tribal, dynastic, religious, or any fight in history, whatever the motives were, could only be ended by tribal, dynastic, or even religious reconciliation, in our time, national reconciliation can only be achieved by people’s desire for national peace. Nothing less than that!

But in order to express national reconciliation, we must first examine the nature of fight between nations. state of national struggle. (Giddens 1985: 103-116) So what is the value basis of the state of national struggle. In our study, we do not immerse ourselves in the pure calculation of power that weaves human struggles in general, although it appears in all human struggles. But it can only become a social organizing idea through a more general set of values. In this age it is largely the national idea. However, the conclusion of national peace is not possible without the birth and spread of national peace and its essence, the consciousness of national togetherness, and the replacement of national relativism and, consequently, the conviction of the potential and realistic nation to fight. Not only in terms of the imagined elements of national identity, but also in their emotions. The challenge of reconciling Hungarians and Slovaks lies in solving this task.

The process of acquiring national identity packs the presentation of right and wrong forms of human behaviour into a fight with the national enemy and enemies. So not only does a person become Slovak, Hungarian, German, Italian in the process of becoming an adult, but as part of the process, he/she learns what heroism, cowardice, loyalty, betrayal is, what is good and what is bad. And in the spirit of national relativism, in a way that is noble in nature, and superior to members of the national enemy. (Spinner 1994: 142) That is because your own culture is real, pure, ancient, that is, more valuable. And the other is inferior, less valuable, and even more radical, dangerous and worthless. Therefore, its destruction, or even its complete destruction, is not a sin but a merit. How to do it is given by the situation. Sometimes by direct violence, other times subtly, by a combination of cultural and administrative and economic means, dressed in peaceful slogans. National separation is also emotional separation. They are experienced by members of different nations, among whom there are many similarities that can be grasped with abstract concepts, but they are unique in their specific emotional experiences. Their poems, songs, anthems are theirs, members of the other nation can only experience their own.

Presenting the other culture as worthless to one’s own national public hinders precisely what would be the main source of its development: the understanding, love, and acceptance by many of the other party’s outstanding cultural achievements. These are studied and known by a narrow layer of experts. But they, for the most part, are also screened so that they can reach their own national public only in a form that does not change national suspicion, does not break down national segregation.

National reconciliation in our age has to mean the parties can draw from each other’s cultures. They can get more from the other than they can gain from hostility. Even nationally. But this can only be imagined and realized if they give up their national aggression towards each other. (Majtényi 2007: 242-244) Without it, they are only able to reconcile interests, not to make real peace and to build national cooperation based on it. But if they give up their national aggression, they can create a relationship based on reciprocity in which helping the other to develop also helps their own development. The strength of the other is my strength. To do this, however, they would have to build a conviction of their belonging, and thus the connectedness of their destiny. In fact, both on their own and in community with others.

This task is undoubtedly enormous. For this reason, it also places restrictions on politicians. In the age of mass politics, a politician cannot break away from the values of the people. If you display and defend something that the public does not understand, and even thinks and feels downright dangerous, you can only create a chance for poli tical success if your offer is both better and more viable than the old one. But in the case of the dominance of a culture of national struggle (Greenfeld 2006: 137-139), one alone cannot do so unless one is highly educated intellectually and extremely ta lented as a politician. It needs social support. However, this requires a cooperation based on the convergence of the intellectual lives of the two nations, and a dialogue and, if necessary, a program of reaching out to the people of the two countries.

The basis of national peace is a sense of togetherness based on close cooperation founded on the interconnection of national cultures. If this brings with it the intertwining of their economies and their political alliance, it could grow into a close federation of states. A country where citizens experience team spirit, togetherness, a sense of belonging, a sense of community, a common fate. Their predecessors in the 19th and 20th century did not understand how valuable is such a development. But that does not mean it can’t now turn in a different direction. The fact that our predecessors did not understand this does not mean that we cannot change it now.

In the meantime, they can get rid of the moral relativism as the basis of the state with respect to national identity and thus its pervasive, crippling effect on the whole society. Instead, they could engage in intensifying global competition through the political and economic weight of their alliance, but above all through the inspiring power of their cultural interconnectedness. (Holton 1998:204)

In the age of the Internet, it is now possible to initiate an exchange of views that differ in essential elements from the ones preferred by the power and those socially dominant. Recognizing the togetherness of nations, especially of the Slovaks and Hungarians, is one of their most important cultural challenges. It depends on them whether they can rise from their minority position in the medium term. And in the long term, along with their neighbours belonging to other nations, their cultural survival makes special sense and takes on a special significance, as they are familiar with both cultures.

Literature

Bergyajev, Nyikolaj 1989. Az orosz kommunizmus értelme és eredete. Budapest, Századvég Kiadó.

Clark, Christopher 2013. Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914. London, Penguin Group.

Figes, Orlando 2002. Natasha´s Dance. A Cultural History of Russia. New York, Metropolitan Books, Picador, Henry Holt and Company.

Holton, Robert J. 1998. Globalization and the Nation-State. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 and London, Macmillan Press.

Giddens, Anthony 1985. The Nation-State and Violence. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Glover, Jonathan 1997. Nation, Identity and Conflict. In: McKim, Robert–McMahan, Jeff (eds.): The Morality of Nationalism. New York–Oxford, Oxford University Press, 11–30.

Greenfeld, Liah 2006. Nationalism and the Mind. Oxford, Oxford Publications.

Hirschi, Caspar 2012. The Origins of Nationalism. An Alternative History from Ancient Rome to Early Modern Germany. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Horowitz, Donald L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Kant, Immanuel 1988. Zum Ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf. In: Kant Immanuel 1988. Rechtslehre. Schriften zur Rechtsphilosophie. Berlin, Akademie-Verlag, 287–338.

Kučera, Rudolf 2008. Közép-Európa története egy cseh politológus szemével. Budapest, Korma Könyvkereskedelmi és Szolgáltató Bt.

Macmillan, Margaret 2002. Peacemakers. The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War. London, John Murray (Publishers).

Majtényi Balázs 2007. A nemzetállam új ruhája. Budapest, Gondolat Kiadó.

Simms, Brendan 2013. Kampf um Vorherrschaft. Eine deutsche Geschichte Europas. 1453 bis heute. München, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

Smith, Anthony D. 2004. The Antiquity of Nations. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Spinner, Jeff 1994. The Boundaries of Citizenship. Race, Ethnicity and Nationality in the Liberal State. Baltimore and London, The John Hopkins University Press.

The Ethnic Composition of Slovakia’s Municipalities, Based on the Data of the 1950 census

Of the Czechoslovak censuses held after World War II, the ethnic data series of the 1950 census are of special importance. The nationality data of the censuses held du ring the party-state period were published only in national, region and district level in some, mostly internal publications of the Czechoslovak Statistical Office. Earlier census publications from 1950 and 1961 were still encrypted. The ethnicity data from the 1950 census are questionable in several ways. According to our calculations, the censuses held shortly after the deportations, reslovakization and population change showed that the number of Hungarians was 113 thousand lower than expected. (Gyurgyík 2011) In the post-World War II period, at all the national, regional and district levels the standing-ground for the particular nationalities and their territorial distribution is reported by the data from year 1961. However, the ethnicity data of Slovakia’s municipalities of the 1961 census (based on statistical office data and archival sources) are not known till this day.2

Nationality (and denominational) data of the 1950 census have only recently become available in the archives of the Slovak Statistical Office. The data were processed from 6 manuscript-type internal publications (hereinafter referred to as „publication”). The publications contain data on each region. Some data of particular settlements of each region are written on A2-size typewritten pages. (See Sčítanie ľudu 1950) The manuscripts containing the data of Slovakia’s municipalities represent the data of 6 nationalities in Slovakia. It indicates the Slovak, Czech, Russian, Polish, German and Hungarian nationalities, which are supplemented by the other category, which is a kind of cover category for Russian, Ruthenian Ruthenian and Ukrainian nationalities.

1. The morphosis of population

The population of Slovakia at the time of the 1950 census was 3 442 317. (Sčítání lidu a soupis domů 1950: 3) According to the 1930 census, its population was 3 329 793. (Sčítání lidu 1930: 23) That means that its number increased by 3.4% between 1930 and 1950. In the period between the 1930 census and the 1946 census, the population barely changed, in fact, slightly decreased. (3 327 803 in 1946; Tišliar–Šprocha 2017: 39) While the population growth was significant in the 1930s, the subsequent loss during the war levelled it out. There was a significant increase also in the international population in the years following the Second World War. Considering the period between 1946 and 1950 only, the population of Slovakia increased by 114,514 or 3.4%.3

The registered data of the number and proportion of nationalities in 1950 do not provide a credible picture from the point of view of the Hungarian, German, and Slovak population, due to the events affecting Hungarians and Germans in Slovakia in the second half of the 1940s. They are rather telling us that after a few years, the disenfranchisement how many people dared to declare themselves Hungarian (or German) at the time of the 1950 census. At the same time, the registered number of the Slovak population is significantly higher than expected.

The last Czechoslovak census before the 1950 one was carried out in 1930, two decades earlier. (In the 1940s, there was a Slovak census in the territory of the Slovak State on December 15, 1940. In Hungary and in the areas annexed to Hungary after the 1st Vienna Treaty (Vienna Award or Arbitration), including the Hungarian-inhabited areas in Slovakia, a census was held in 1941.) Especially during the “long forties” of these two decades often contradictory processes influenced the lives of different social groups and nationalities of the population, and “községsoros” (i.e. municipal) demographic consequences we did not have data on.4 (Entry and expulsion of so called ”anyások”5; deportation of Jews, Holocaust; forced departure of Czechs from Slovakia; departure of Slovaks and Czechs from the territories returned to Hungary; deportation of Hungarians and Germans; re-Slovakization of a significant part of the Hungarian population also significantly reshaped the ethnic composition of the Slovak population.) All these changes can be felt in the differences in ethnic data sets of the two censuses.

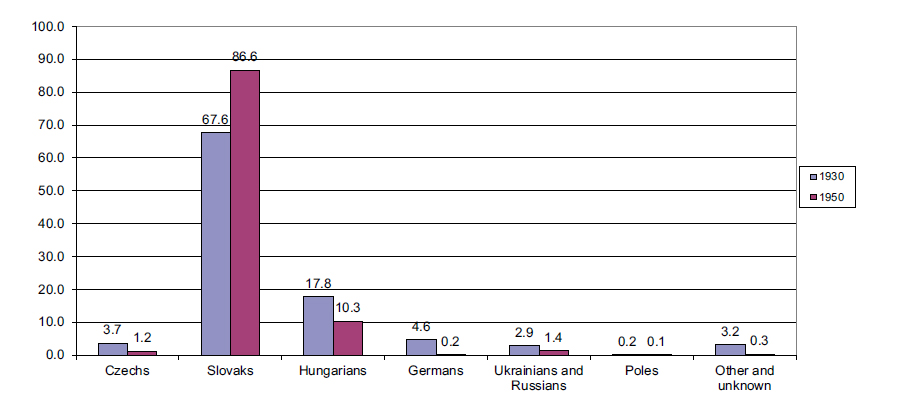

Diagram 1: The change of proportion of nationalities in Slovakia 1930, 1950, %

During the two decades (between 1930 and 1950), the registered number of Slovaks increased unrealistically from 225,138 to 298,254 by 73,116 people, or 32.5%. Their proportion increased from 67.6% to 86.6%. The number and proportion of other identified nationalities decreased. The number of Hungarians decreased from 592,337 to 354,532, by 237,805 people, by 40.2%, and their proportion decreased even more from 17.8% to 10.3%. The number of Czechs fell by 1/3 from 121,696 to 40,365, and their number from 3.7% to 1.2%. The number of Germans dropped to 1/30 in 1950, from 154,821 to 5,179. Their statewide share shrank from 4.6% to 0.2%. But the number and proportion of other identified nationalities also declined. (See Table F1 in the Appendix.)6

The census held after the deprivation of the rights of Hungarians does not provide usable data on the Hungarian population, it rather provides information on how many people actually dared to confess their Hungarian identity in such a short time after the austereness affecting the Hungarians as a whole. (Gyurgyík, 2011)

1.1. Regions and districts

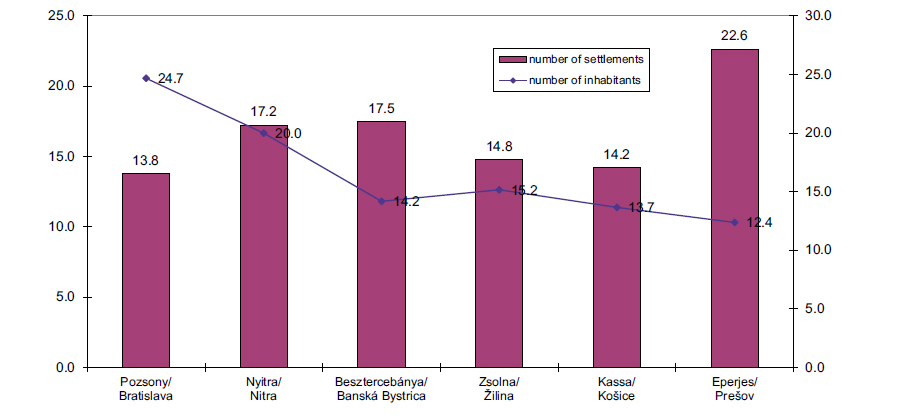

In 1950, at the time of the census, there were 3344 municipalities (villages and towns) in Slovakia. The number of localities and the population of Slovakia varied significantly considering the regions. The country was divided into 6 regions and at the lower level 91 districts. The number and proportion of localities (villages) and inhabitants of the regions differed significantly. Most settlements were located in the region of Eperjes (Prešov)7 (757), 22.6% of the settlements of Slovakia. The smallest number of settlements was found in the region of Pozsony (Bratislava) (460), which was 13.8% of the country’s localities. The distribution of the population is the opposite. Most of them lived in the region of Pozsony (Bratislava) (849,282 people) 24.7%, and half as many in the region of Eperjes (Prešov) (425,494 people) 12.4%. There is also a significant difference in the proportion of settlements and population of the region of Besztercebánya (Banská Bystrica). The localities belonging to the region of Besztercebánya (Banská Bystrica) accounted for 17.5% of the municipalities in Slovakia (584 settlements), while 14.2% of the country’s population lived in this region (487,903 people). The proportions of the localities and population of the other 3 regions are less divergent. (Diagram 2. See also Table F2 in the Appendix.)

Diagram 2: The proportion of settlements and inhabitants in Slovakia according to dist ricts in 1950, %

The number of districts belonging to each region showed less variation. The Pozsony (Bratislava) region contained 17 districts, while the Kassa (Košice) region included 13. The number of municipalities within each district varies greatly. On average, 36.7 places (municipalities) are per region. There are two districts with only one locality (Pozsony [Bratislava] and Magas-Tátra [Vysoké Tatry]). Most of the localities were in the Kassa (Košice) region (93 municipalities). The highest number of inhabitants were found in Pozsony-város (Bratislava-mesto) which had a district status, with 192,896 inhabitants.8 5.6% of the Slovak population lived here. The region of Szepesóvár (Spišská Stará Ves) had the lowest population of 9,163 or 0.3% of the country’s population.

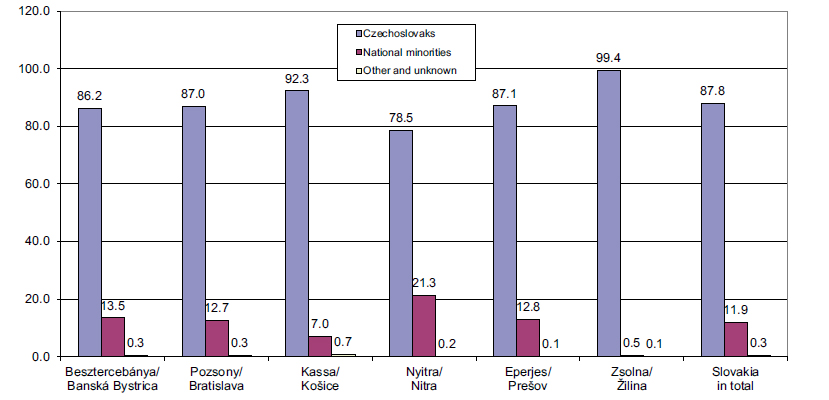

When examining of nationalities by regions, the nationalities are divided into two groups. (In addition, data for the very low proportion of other and unknown categories are also included). The majority nationalities include the Czechs and Slovaks, hereinafter referred to as “Czechoslovaks”, and the other registered nationalities are the “national minorities”. From the data we can see that the largest proportion of national minorities lived in the Nyitra (Nitra) region (21.3%) and the least in the Zsolna (Žilina) region (0.5%). In most regions, the proportion of national minorities exceeded 10%. Besztercebánya (Banská Bystrica) (13.5%), Pozsony (Bratislava) (12.7%), Eperjes (Prešov) (12,8%). After the Zsolna (Žilina) region, the proportion of minorities is the lowest in the Kassa (Košice) region (7.0%). The proportion of those in the category of others and unknowns is very low (0.1%-0.3%).

Diagram 3: The proportion of groups of nationalities in Slovakia according to regions in 1950, %

In the following we will review the composition of the ethnic configuration by district, that is, examine the ethnic distribution of each region. We use the following categorization to examine the ethnic configuration of the district.9

In 1950, 81 out of the 91 districts in Slovakia had a Czechoslovak majority, with only 10 regions not having a majority of Czechs and Slovaks. They formed a qualified majority in 69 out of the 91 districts. In most districts (in 59) nationalities were in diasporas. In 46 of these, their proportion was less than 2%, and in 13 districts their proportion varied between 2% and 10%. They were in 16 regions a slight minority and in 6 regions a strong minority. They were a slight majority in 10 districts. None of them were a qualified majority.

1.2. Size groups of settlements

The population living in Slovak settlements varied widely. Most of the inhabitants were from the city of Pozsony (Bratislava) (192,896 people), and the fewest lived in the village of Bálintfalva (Valentová, belonging to the Túrócszentmárton [Turčianský Svätý Martin] region, 32 people).

In the following, we examine the composition of the settlements according to the size groups of the population.

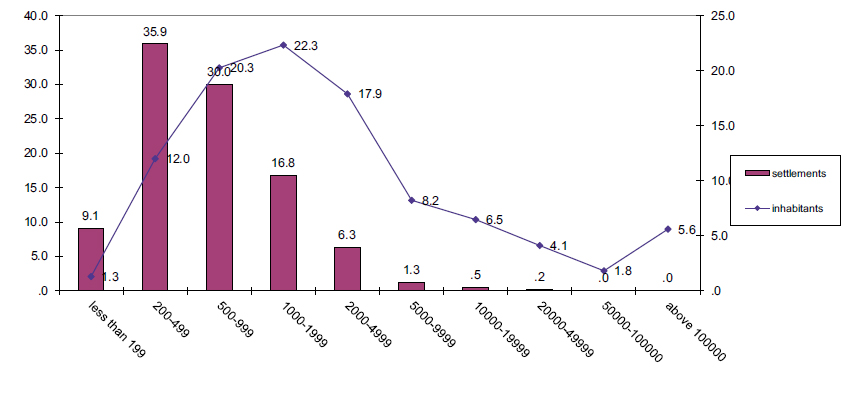

Diagram 4: Distribution of population of Slovakia according to the size groups of settlements in 1950, %

Three quarters of the settlements in Slovakia were settlements with less than 1000 inhabitants. The largest number was of the settlements with 200–499 inhabitants (1200, 35.9%), and the number of villages with 500–999 inhabitants (1002, 30.0%). There was a significantly lower number (562) and proportion (16.8%) of villages with 1000–1999 inhabitants. The number of localities with a population of more than 5,000, which can be considered urban, was very low (67 localities, 2%). Only the two largest cities (Pozsony [Bratislava] and Kassa [Košice]) had a population of more than 50,000. Nearly a quarter (22.3%) of the population lived in small villages with 1000–1999 inhabitants, more than fifth (1/5) in small villages with 500–999 inhabitants (20.3%), and 17.9% in places (municipalities) with 2000–4999 inhabitants. 18,8% of population lived in the cities with 5000–49999 inhabitants, 5,6% lived in Pozsony (Bratislava), and 1,8% lived in Kassa (Košice). (See also Table F3 in the Appendix)

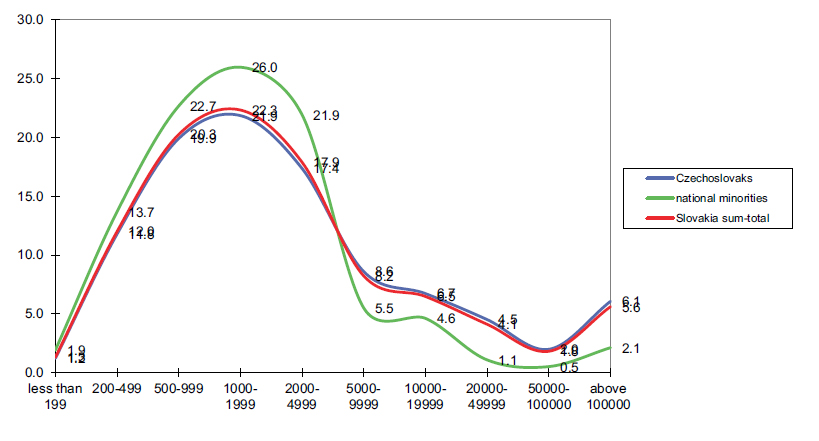

Diagram 5: Proportion of national groups of Slovakia by size groups of settlements in 1950, %

It can be observed within the population of Slovakia that the degree of urbanization of national minorities is lower than the national average. The proportion of national minorities is declining towards larger localities. Their proportion is higher in localities with a population of less than 5,000 than in the local population, and it is much lower in localities with a larger population. (See Table F3 in the Appendix)

Their proportion is the highest in settlements with a population of less than 200 (17.6%). But the decline is not continuous. Their rate is slightly lower in localities with 2000–4999 inhabitants (14.6%), while their scale (percentage) in localities with 500–1999 inhabitants ranges from 13% to 14%. Their proportion is much lower in localities with a population of more than 5,000. In cities with 5000–19999 inhabitants, their rate is above 8%, in cities with 20-100 thousand inhabitants it is above 3%, while in the only city with more than 100,000, Pozsony (Bratislava) is 4.5%. The difference between Czechoslovakians and national data is very small. Their proportion is higher in localities with a population of more than 5,000, while it is lower in localities with a lower population. This difference is only a few tenths of a percentage point. (Diagram 5)

2. Ethnic structure

So far we have classified the Slovak nationalities into two groups: we have distinguished the majority and minority nationalities. The first was the aggregate data of the Czechoslovakians (or “Czechoslovaks”), and the second was the aggregate data of the other nationalities (Hungarian, Russian, German, Polish and other nationalities). Let us examine the ethnic structure of these two groups of nationalities.

First we look at the number of settlements in which Czechoslovaks and those belonging to other national minorities live. In 1950, out of 3344 settlements, 3,339 had at least 1 inhabitant of Czechoslovak nationality. The missing 5 settlements were populated only by Russians. In the case of national minorities, at least 1 person belonging to one of the national minorities lived in 2018 settlements out of the 3344, i.e. the number of settlements inhabited by Czechoslovakians only was 1326.

2.1. Majority and minority nationalities

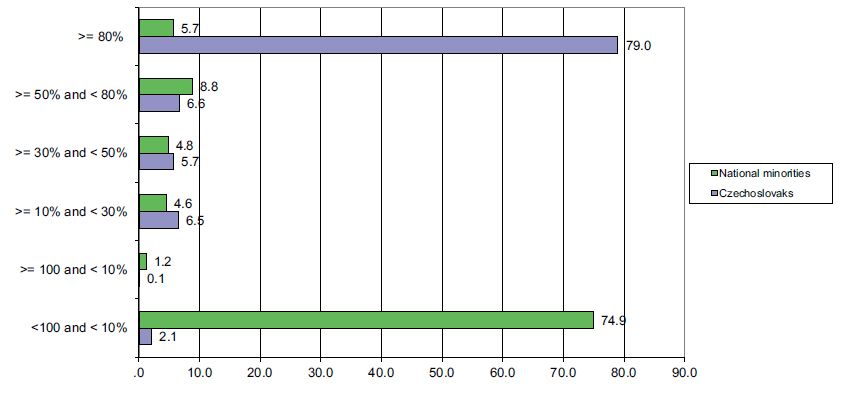

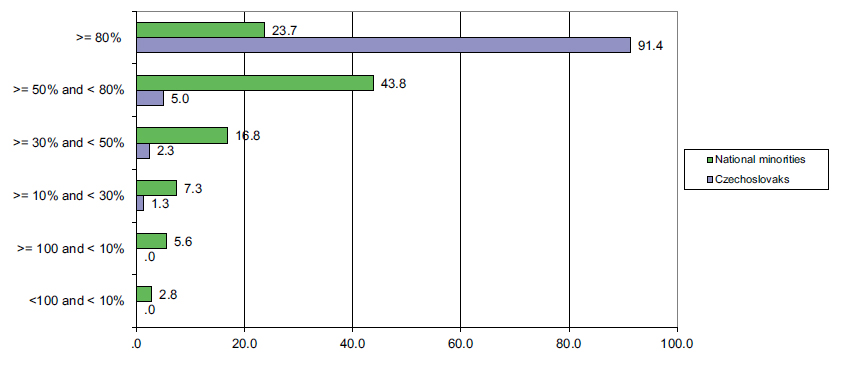

Diagram 6: The distribution of Czechoslovaks and national minorities according to the number and proportion of nationalities in settlements, 1950, %

In the following, we will examine the proportion of the majority and minority nationalities in the settlements of Slovakia. The ethnic structure will be analysed on the basis of a 6-categories-criteria system.10

Czechoslovaks lived mainly in settlements (78.9%) where they formed a dominant majority (their proportion is higher than 80%). On the other hand the vast majority of settlements inhabited by national minorities (76.9%) were sporadic settlements, ie their proportion was lower than 10% in the vast majority of settlements inhabited by nationalities. In 1950, out of 2018 settlements inhabited by minorities, in 1220 settlements their rate did not reach 10%. Of the 3344 settlements, in 2546 settlements the proportion of nationalities was less than 10%.

The number of municipalities with a majority of national minorities was 485, i.e. 14.5% of the municipalities in Slovakia had a majority of national minorities. (Diagram 6)

Diagram 7: The distribution of Czechoslovaks and national minorities according to the number and proportion of nationalities in settlements, 1950, %

Compared to the previous approach, when we examined the distribution of settlements according to the proportion of nationalities, a much more striking feature of the ethnic structure is the distribution of nationalities according to the ethnic proportion (composition) of settlements. From this point of view, we can observe completely different characteristics: 8.4% of nationalities lived in sporadic and in sporadic settlements. By contrast, 67.4% of them in 1950 lived in settlements dominated by minorities. The proportion of the Czechoslovak population in sporadic settlements is almost negligible, 0.1%, it was also very low at 3.9% in the settlements inhabited by their minority. It accounted for 5.0% in the slight majority settlements and 91.4% in the strong majority settlements.

3. Ethnic composition of Slovakia

3.1. Regions

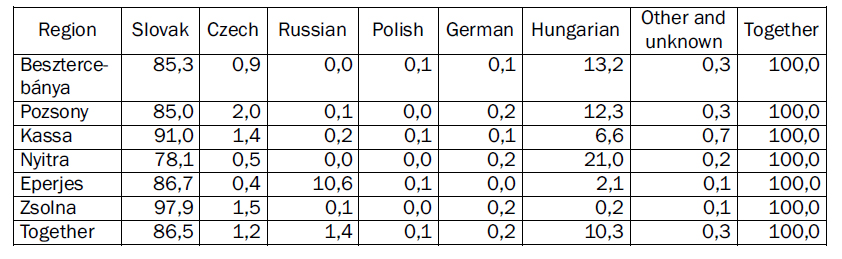

Table 1: The distribution of the nationalities of Slovakia by regions, 1950

As mentioned, the 1950 census data of Slovakia’s municipalities showed data for 6 nationalities, supplemented by other and unknown categories. The 6 nationalities differed greatly in number as well as territorial distribution. Let us look at the morphosis of the number of individual nationalities by regions.

The proportion of Slovaks was the highest in the districts of Zsolna (Žilina) and Kassa (Košice) (97.9% and 91.0%). The proportion of Hungarians was the highest in the Nyitra (Nitra) region, 21.0%. The largest number of Russians lived in Eperjes (Prešov) region (10.6%) and the most of Czechs in the Pozsony (Bratislava) region (2.0%). The proportion of other nationalities is very low, none of them exceeding 0.1–0.2% in each region. (See also Table F2 in the Appendix)

3.2. Districts

In the following, we discuss the shaping of the distribution of Slovak nationalities by dist ricts. Our discussion, however, will be limited to those nationalities that constitute a significant proportion (at least 2%) in at least 1 district.

The proportion of one nationality, that of Poles does not reach 2% in any district, so we do not deal with their distribution by districts. The proportion of those in the other and unknown category is higher than 2% in two districts. Most probably, the Germans in the Késmárk (Kežmarok) district and some of the Hungarians in the Nagyrőce (Revúca) district did not declare their national affiliation and thus their proportion increased.

However, the distribution of the other 5 nationalities differs significantly. Slovaks were in the majority in 80 of the 91 Slovak districts. They had a qualified majority in 68 districts and a slight minority in 12 districts.

The proportion of Hungarians was lower than 10% in 66 districts, ranged from 10% to 50% in 17 districts, and made up the majority of the population in 8 districts, in none of which did they constitute a qualified majority.

The Russians were in a slight minority in 4 districts and in a slight majority in two districts. The proportion of Czechs was higher than 2% in 12 districts. In one of these districts (High Tatras), they were in a slight minority.

The proportion of Germans exceeded 2% in two districts: Stubnyafürdő (Turčianské Teplice) and Privigye (Prievidza).

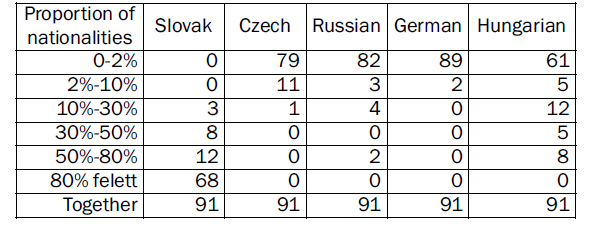

Table 2: Distribution of districts in Slovakia by proportion of nationalities living in district groups in 1950

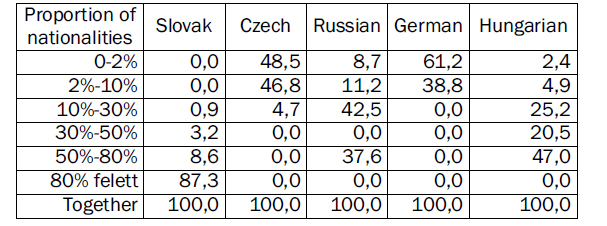

Now we examine the distribution of nationalities according to their proportion within districts. We can see from the data that the distribution of the nationalities involved in the study is quite diverse according to the ethnic composition of the districts. The vast majority of Slovaks (95.9%) lived in Slovak-majority districts. (Of these, their share is 87.3% in qualified majority districts and 8.6% in slight majority districts). 0.9% of them lived in strong minority districts. Nearly half of Hungarians (47.1%) lived in slight Hungarian-majority districts, and a similar proportion (45.7%) lived in Hungarian-mino rity districts. 7.3% of Hungarians lived in scattered districts. 37.6% of Russians lived in mild majority districts. 42.5% of them lived in mild minority districts and almost 1/5 (19.9%) in sporadic districts.

The vast majority of Czechs lived in sporadic districts. Only 4.7% lived in a district with a slight Czech minority (in the city of Pozsony [Bratislava]).

Table 3: Distribution of nationalities in Slovakia by proportion of nationalities living in district groups 1950, %

3.3. Settlements

Henceforwards, we examine the composition and distribution of nationalities in Slovakia and the development of the proportion of nationalities living in cities or towns at the level of settlements.

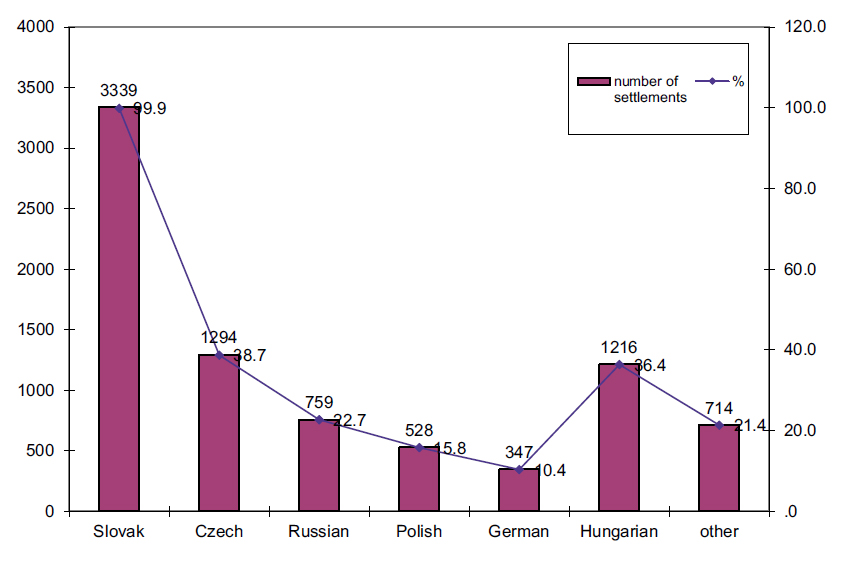

Diagram 8: The number and proportion of settlements inhabitated by each nationality in 1950

Firstly we examine how many settlements of each nationality were detected (in what proportion) in each settlement (i.e. we consider the municipalities where there lived at least one person from each nationality).

People of Slovak nationality lived in almost all settlements; in 1950, there were only 5 settlements (out of 3,344) without Slovak inhabitants, all of which were inhabited by Russians only. Czechs were present in 1294 municipalities, 38.7% of the settlements. Hungarians were found in a slightly smaller number of settlements, in 1216 municipalities (36.4%). Russians lived in 22.7% of settlements, Poles in 15.8% and Germans in 10.4%. (Other and unknown nationalities were detected in 21.4% of the localities).

3.3.1. Degree of urbanization

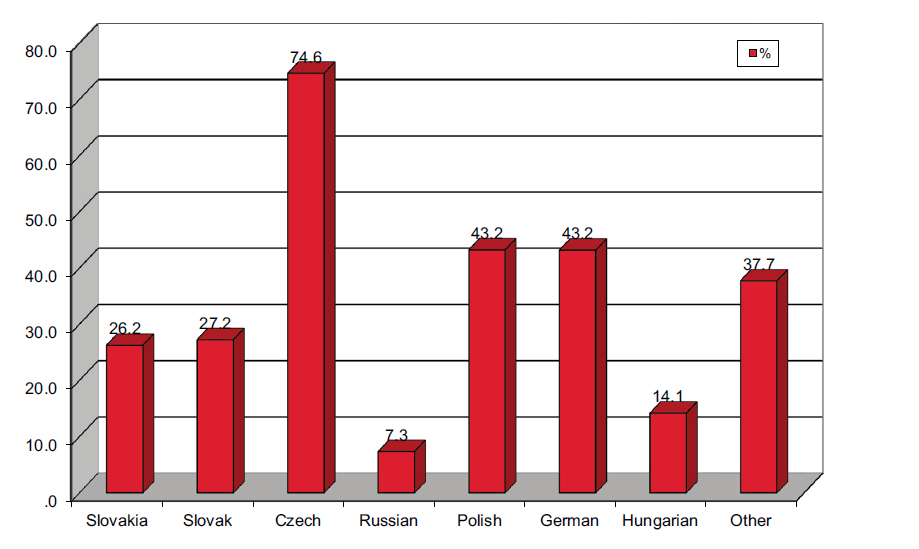

In what follows, we will look at the proportion of each nationality living in villages, respectively, towns. Whether members of a particular nationality will be considered rural or urban dwellers is not based on the legal status of the municipality in question; instead, settlements with less than 5,000 inhabitants are statistically considered to be villages and over 5,000 inhabitants are statistically considered to be towns. In Slovakia, in 1950, 26.2% of the population lived in cities or towns.

Diagram 9: The proportion of population living in cities according to nationalities in 1950, %

The under- and over-urbanization of each nationality compared to the country-wide average was very different. The Czechs were the most urbanized, with the largest proportion living in cities. Nearly ¾ (74.6%) of them lived in cities. This fact can be connected to the historical peculiarities of Czechoslovak social development.11 The proportion of towners among Slovaks is slightly higher than the national rate (27.2%). But members of some small scattered nationalities also lived in cities at a much higher rate than the country-wide: the proportion of Germans and Poles was the same in cities (43.2%). The settlement structure of the Germans was more urbanized than that of other nationalities for centuries, while in the case of the Polish migration to cities was more characteristic. The nationality living in towns in the lowest proportion were the Russians (7.3%), living in one of the most undeveloped regions of the country, and this is also reflected in their settlement structure. There are also historical reasons for the under-urbanization of the Hungarian population (14.2%).12

We get an even more detailed picture of the degree of urbanization of nationalities, their distribution according to the proportion of people living in cities and villages, if we take a look at the patterns of the distribution of nationalities according to the size groups of settlements. (See Table F4 in the Appendix)

3.3.2. Ethnic structure

In this section, we examine the ethnic structure of each nationality according to settlements. In our analysis, we analyze the ethnic structure of nationalities from two pers pectives: firstly, we examine the distribution of each nationality according to the ethnic nature of the settlements; secondly, according to the number of nationalities living in the settlements.

The Slovak nationalities are divided into 2 groups according to their ethnic structure. The first includes those that have the full spectrum of ethnic structure, i.e. all size groups include settlements where these nationalities live. Only 3 nationalities can be classified in the first category from this point of view: Slovaks, Hungarians and Russians. Group 2 includes those nationalities that have a distorted ethnic spatial structure, ie they live mostly only in sporadic settlements, incidentally living in a mino rity in some other settlements.

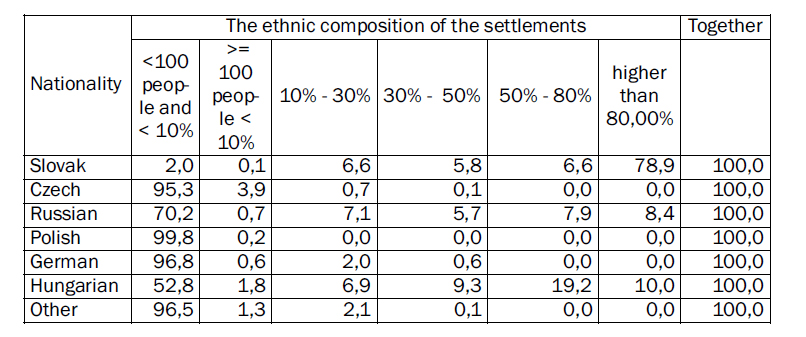

Table 4: Distribution of localities inhabited by nationalities of Slovakia according to ethnic composition of settlements 1950, %

From the data in Table 4 we can see that – disregarding Slovaks – the majority of settlements were inhabited by certain nationalities whose proportion is less than 10% and their population is less than 100 people. In the case of Slovaks, the proportion of such settlements in 1950 was 2.0%. The majority of settlements inhabited by Hungarians also belonged to this group. Among other nationalities, the proportion of Russians is still the most favorable: 70.2% of the settlements inhabited by them belonged to this group of scattered settlements. More than 90% of the settlements inhabited by other nationalities fell into this category of settlements.

We can also see that a relatively small proportion of settlements falls into the other category of sporadic settlements, where the proportion of individual nationalities is less than 10%, but their population is higher than 100 people: their proportion is highest among Czechs (3.9%) and Hungarians (1.8%). Members of other nationalities live in an even smaller proportion in these settlements.

Not all registered nationalities disposed of settlements where the individual nationality was in a slight minority. Among the nationalities we examined, the proportion of Poles does not exceed 10% in any of the villages inhabited by them. The proportion of settlements where certain nationalities live in a slight minority (10%–30%) is highest among Russians (7.1%), Hungarians (6.9%) and Slovaks (6.6%).

Their proportion exceeds 1% for Germans (2.0%). Only a very small number of sett lements falls into this category (9 localities) of the localities inhabited by Czechs, as a result of which their proportion is negligible (0.7%). In 1950, 5 nationalities shared sett lements where the proportion of the studied nationalities ranged from 30% to 50%. Apart from Hungarians (9.3%), Slovaks (5.8%) and Russians (5.7%), there were 9 sett lements inhabited by Czechs and 7 inhabited by Germans exceeding 30% (0.1%, respectively 0,6%). Three nationalities belonged to the nationalities that formed a majority in settlements: besides the Slovaks, the Hungarians and the Russians. The proportion of settlements with a slight majority is 19.2% for Hungarians, 7.9% for Russians and 6.6% for settlements inhabited by Slovaks in a similar proportion.

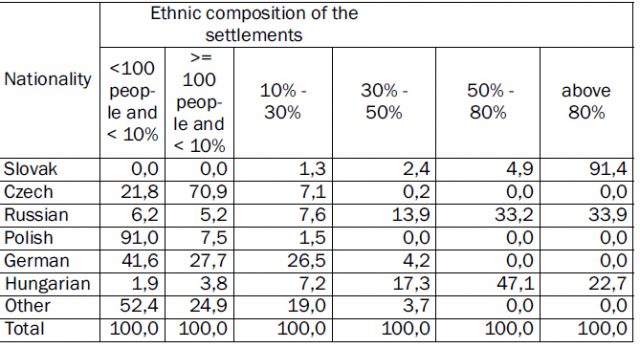

Settlements with a qualified majority included 78.9% of the settlements inhabited by Slovaks, 10.0% of the settlements inhabited by Hungarians, and 8.4% of the settlements inhabited by Russians. Now, we take a look at how the population of each natio nality is distributed according to the ethnic composition of the settlements. (Table 5) The distribution of the settlements -inhabited by nationalities and those belonging to each nationality – differs significantly according to the ethnic composition of the settlements. According to the ethnic composition of the settlements, the distribution of the Slovak population is the highest. 91.4% of them lived in places where their proportion exceeded 80%. Another 4.9% lived in settlements with a slight Slovak majority. The proportion of Slovaks in areas where they are not in the majority is negligibly low: 3.7%.

In 1950, the relative majority of Hungarians in Slovakia lived in settlements with a slight Hungarian majority (47.1%). Nearly a quarter (22.7%) of them lived in localities with a qualified Hungarian majority. At the same time, we can observe that the proportion of Hungarians is gradually decreasing in the direction of scattered settlements. Nearly a quarter of Hungarians (24.5%) lived in settlements with a Hungarian minority, 5.7% in sporadic localities.

In the case of Russians, a greater degree of scattering is observed. The proportion of people living in sporadic settlements is 11.4%, and of those living in minority settlements is 21.5%. In 1950, more than two-thirds (67.1%) of the Russian population lived in settlements where they were also in a statistical majority. Of this, the proportion of people living in qualified majority settlements was 33.9%. None the other nationalities, as already mentioned, lived in majority settlements. 7.3% of Czechs lived in minority settlements, the vast majority (92.7%) lived in diasporas. A non-negligible proportion of Germans lived in 1950 in German-minority localities (30.7%). More than 2/3 of them (69.3%) lived in diaspora. 1.5% of Poles lived in a slightly minority settlement. The vast majority of them were scattered.

Table 5: Distribution of Slovak nationalities according to the ethnic composition of the settlements, 1950, %

The ethnic structure of the nationalities living in Slovakia is further examined according to the size groups of the number of nationalities living in the settlements. (Diagram 9) That is, we focus on how the settlements inhabited by each nationality are distributed according to the number (size groups of the number) of the nationalities living in the villages, as well as on how high the population of each nationality is in these settlements. In the first approach, the size groups of nationalities living in the settlements were considered according to the same system of categories as the one applied in Chapter 1.2.13 In this approach, in the case of Poles and Germans, we found only a very small number of settlements where their number was more than 199. Therefore, we developed a more appropriate category system for the purpose of our study. That is, the first, smallest range of the previous category system, from 0 to 199 people, was further divided into smaller units. (We created the following categories: 1; 2-4; 5-9; 10-19; 20-49; 50-99; 100-199.) The formation of the new categories follows the logic of the previous category system. As a result, the distribution of individual nationalities can be traced by groups of up to a few people in each settlement. (See Diagram 9, and also Table F5 in the Appendix)

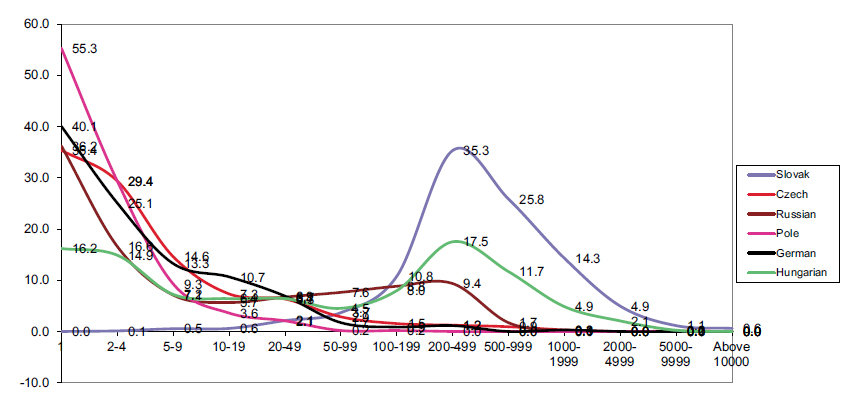

Diagram 10: Distribution of settlements inhabitated by nationalities according to the sizegroups of the nationalities living there in 1950, %

The data show that the data of the Slovak population are closest to the normal distribution. The largest proportion (35.3%) lives in communities with 200–499 and (25.8%) in settlements with 500–999 people per settlement. In the case of Hungarians, also the group of 200–499 people is the largest, but this is followed by scrap groups of 1 and 2-4 people (16.2% and 14.9% respectively), only followed by groups of 500–999 people (11.7%). In the case of other nationalities, shreds of low numbers in each sett lement are the most numerous.

Among Russians, shreds of 1 and 2-4 people are the most numerous (36.2% and 16.6% respectively), then the categories with 5–499 people occur in almost identical proportions (their proportions are between 5.7% and 9.4% respectively) In the case of scattered nationalities, it can be observed that shreds of 1 and then 2-4 people are the most common, their number decreases rapidly as moving on towards larger communities. In the case of Poles and Germans, the proportion of 1-person shreds in the settlements inhabited by these nationalities is approximately 55.3% and 40.1%, respectively, and the proportion of 2-4 people is more than ¼.

Next, we examine the distribution of the number of persons belonging to natio nalities according to their size groups in the settlements.

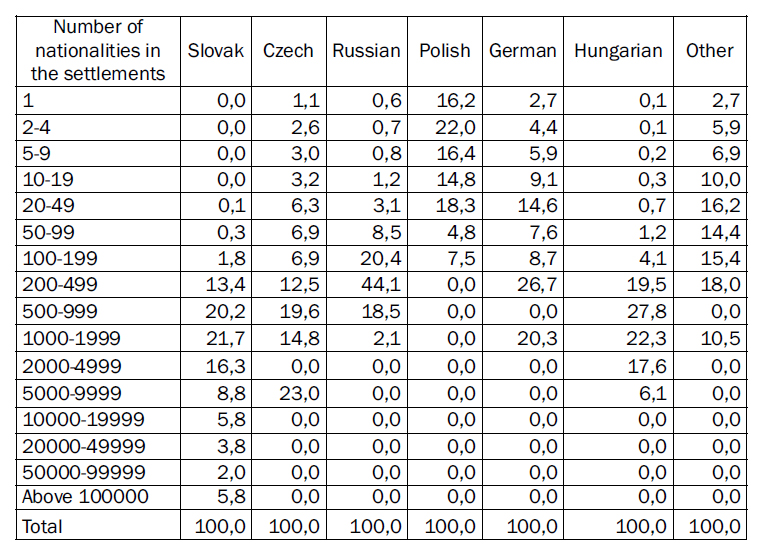

Table 6: Distribution of nationalities in settlements inhabited by nationalities according to the size groups of nationalities living there 1950,%

In the case of Slovaks, we can observe that in those settlements where their number does not reach 200, their proportion is very low. As the distribution of Slovaks follows national trends to a very large extent, these cases are mainly small dwarf villages. The majority of Slovaks lived in communities between 500 and 4999 (58.1%), the vast majority of which are villages, but the proportion of Slovak communities in small, medium and large settlements is also relatively proportional (5000–19999 people: 14.6%, 20,000–99,999 people: 5.8%, over 100,000 people: 5.8%).

Almost 1/4 of the Czechs (23.1%) lived in communities of less than 100 people, more than 1/3 (39.1%) in communities of 100–999 inhabitants, 14.8% in communities of 1,000 and 4,999 residents, and 23.0% (9,296 people) – equal to the population of a small town – lived in Pozsony (Bratislava) alone. 83.0% of Russians lived in settlements with numbers ranging from 100 to 9999. 14.9% lived in localities with less than 100 people, and 2.1% in places with numbers between 1,000 and 1999. In the case of Poles, the very contrary process can be observed: the largest number lived in shreds of 2-4 people (22.0%), after that their number decreases, 4.8% lived in communities of 50–99 people. Most of them lived in Pozsony (Bratislava) (135 people, 7.5%).

In the case of the Hungarian population, we can also observe that with the increase of their number is accompanied by an increase in their proportion in the loca lities. 4.1% of Hungarians live in localities numbering 100–199 Hungarians, and their number is growing rapidly in the following size groups. Most (27.8%) of them lived in communities of 500–999, their share decreased slightly in the next two size groups, and then their proportion in communities between 5000–9999 was 6.1%. The number of Hungarians exceeded 5,000 in three cities: Gúta (Kolárovo) (7748 people), Komárom (Komárno) (7077 people), Pozsony (Bratislava) (6823 people).

The proportion of Germans is also increasing almost continuously in successive size groups. The largest number lived in the groups of 200–499 (26,6%) and 1000–1999 people (20.3%).

Summary and outlook

In 1950, 20 years after the 1930 census, the first post-World War II census took place. The so called ”községsoros” (see Footnote No 4) ethnic data were not known as they were not published. The nationality data sets of the census bear the imprint of the events of the long 40 years in the evolution of the number of individual nationalities. The registered data showed the number of Hungarians and Germans significantly lower than their expected number, while that of Slovaks significantly higher. Even if they reflect the real ethnic conditions in a distorted and questionable way, the data series indicate a very large transformation of the ethnic structure: the composition of settlement patterns of demographically negatively affected nationalities has changed signi ficantly; the number and proportion of Hungarians living in cities, Hungarian-majority administrative units and settlements, Hungarian communities living in the settlements decreased, the ethnic bloc areas with significant dimensions in the 1930s became fragmented, their borders blurred, and signs of scattering appeared. The discussion of these changes, however, is a subject of further research.

Literature

Administrativní lexikon obcí republiky Československé 1955. Podle správního rozdělení 1. ledna 1955. Praha, Státní úřad statistický a ministerstvo vnitra.

Gyurgyík, László 1994. Magyar mérleg. A szlovákiai magyarság a népszámlálási és a népmozgalmi adatok tükrében. Pozsony, Kalligram.

Gyurgyík, László 2011. A szlovákiai magyar lakosság demográfiai változásai 1949 és 1963 között, különös tekintettel a népmozgalmi folyamatokra In: Hushegyi, Gábor (szerk.): Magyarok a sztálinista Csehszlovákiában 1948–1963. Pozsony/Bratislava, Hagyományok és Értékek Polgári Társulás, 26-41.

Retrospektívny lexikon obcí ČSSR 1850-1970, 1978; počet obyvatelů a domů podle obcí a částí obcí podle správního členění k 1. lednu 1972 a abecední přehled obcí a část obcí v letech 1850-1970. 2. diel: Abecedný prehľad obcí a částí obcí v rokoch 1850-1970. 2. zv., Slovenská socialistická republika. Praha, FŠÚ.

Sčítání lidu v republice Československé ze dne 1. prosince 1930. Díl I. 1934. Praha, Státní úřad statistický.

The Ethnic Composition of Slovakia’s Municipalities… 33

Sčítání lidu a soupis domů a bytů v republice Československé ke dni 1. března 1950. Nejdůležitější výsledky sčítání lidu a soupisu domů a bytů za kraje, okresy a města. Díl I. 1957. Praha, Státní úřad statistický.

Sčítanie ľudu 1950. Plocha, vek, povolanie, pomer k povolaniu, národnosť a náboženské vyznanie obyvateľstva podľa obcí. Bratislava (Nitra, Banská Bystrica, Žilina, Košice, Prešov), manuscript.

Statistický lexikon obcí republiky Československé 1955 Podle správního rozdělení 1. ledna 1955, sčítání a sčítání domů a bytů 1. března 1950. Praha, Státní úřad statistický a ministerstvo vnitra.

Tišliar, Pavol–Šprocha, Branislav 2017. Premeny vybraných charakteristík obyvateľstva Slovenska v 18.–1. pol. 20. storočia. Bratislava, Muzeológia a kultúrne dedičstvo, o. z. v spolupráci s Centrom pre historickú demografiu a populačný vývoj Slovenska Filozofickej fakulty Univerzity Komenského v Bratislave.

The Primary Results of the last Hungarian Identity Survey in Slovakia

1. Survey and sample

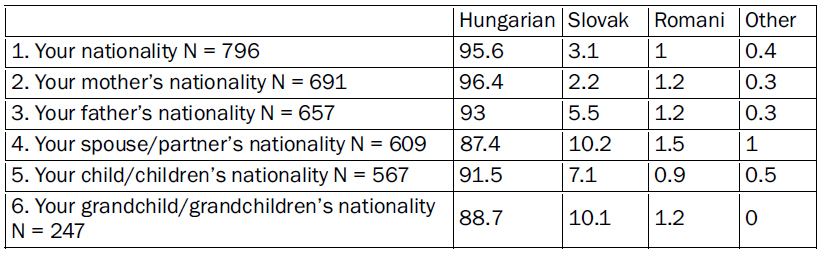

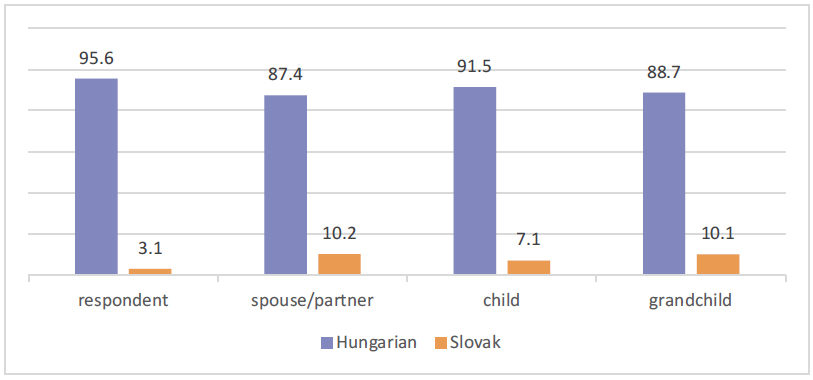

In June 2018, the Department of Sociological and Demographic Research of the Forum Institute of Minority Research and the National Policy Research Institute in Budapest conducted a questionnaire survey in 16 districts of southern Slovakia2 in a total of 120 settlements, as well as in Bratislava and Košice. The sample consisted of 800 adult Hungarians from Slovakia. The sample is representative in terms of gender, age group, education, type of settlement, and the share of the Hungarian population per district in the mixed-population districts of southern Slovakia.

Of the sample 47.2% were men and 52.8% were women. As for the age groups, for the sake of comparability with previous surveys, three age groups were used as the basis for sampling: aged 18–34 (27.4%), aged 35–55 (39.3%), and over the age of 55 (33.3%). Regarding education, 22% of respondents had a primary education, 28% had a high school education without a high school diploma, 34% had a high school diploma, and 16% had a higher education. Regarding the type of settlement, 38% of the respondents live in a city or a town and 62% in a village.

The primary goal of the survey was to monitor the development of national values and national identity, which we have been researching for a long time, as well as the most important background factors and their impact.

In the following, we briefly describe some of the subjective indicators of the respondents’ living conditions, quality of life, and feelings of life; then we characterize their current public attitudes. Afterwards, based on the primary results, we present the most important issues of national values, national identity, and opinions about the Hungarian existence in Slovakia, as well as language use and school choice.

The aim of this paper is to present the preliminary results so that they can be accessed and used by others as source data. Unless otherwise indicated, the results are expressed as a percentage.

2. Living conditions, quality of life, feelings of life

One of the basic factors of the quality of life is health condition. The subjective health condition of the respondents is not the health condition measured by objective me dical devices, but what they themselves perceive. In accordance with this, 75% of them consider themselves to be healthy, of which 31% have not been ill for a long time, and 44% become ill once or twice per year. Moreover, 8% of respondents are often ill but have no major problems, 11% are under constant treatment, and 5% are disability pensioners.

In our previous surveys3, we addressed health protecting and health harming determinants several times within the lifestyle issues. Due to space constraints, only a few of these indicators were included in the questionnaire this time, specifically a few questions about eating habits, sports, and smoking. Regarding eating habits, it is favorable that the majority of respondents (80%) eat regularly, i.e. either three times per day – breakfast, lunch, dinner (56%), or five times per day (24%), supplementing the three meals with 10:00AM and afternoon snacks. The majority most often consume Hungarian (84% often, 15% sometimes) and Slovak meals (37% often, 57% sometimes). The third most popular is Italian cuisine (15% often, 60% sometimes). As for the unhealthy “fast” foods (e.g., McDonald’s), 5% consume them often, 48% sometimes, and 48% never.

The most common way to spend free time is via family programs, namely active social programs, such as joint trips, cooking together, and conversations. These were mentioned by 30.4% of the respondents. This is followed by cultural activities, such as reading, watching movies, listening to music (21.4%), meeting and having fun with friends (18.5%), pursuing a favorite hobby (13%), and lastly playing sports (4.6%). Of the respondents, 12% indicated that they did not have much free time to devote to themselves.

The fact that sport is not a frequent activity is shown not only by its low share among free time activities (barely 5%), but also by the answer distributions of a separate question focused on this. When asked how often they used to do sports in their free time, the results were the following: 5% answered daily, 15% at least three times per week, 49% rarely, and 31% never. “Rarely” (i.e., fewer than three times per week) is also scarce because, according to the WHO, one needs to move for at least 30 minutes three times per week. In other words, 80% of Hungarians in Slovakia move less than is needed. However, 30% smoke (EU average is 28%), of which 15% do so conti nuously or frequently.

The impact of social relationships on the quality of life is well known. With regard to the most intimate relationships (i.e., the family), the majority of the respondents (64%) live in a permanent partnership, mostly married (54%), and the rest in a coha biting relationship (10%). Of the respondents, 23% are unmarried, almost 10% are divorced, and 4% are widowed. In addition, 71% of the respondents have children and 31% have grandchildren.

One of the manifestations of the quality of social relationships is whether there is a person we can rely on in everyday life situations. Of the respondents, 86% have such people in their lives, of which 47% answered that there are more such people, and 39% know about one such person. However, 14% of the respondents do not always perceive this social support, and there are also those (1.3%) who have no one to rely on. Here we would also mention transcendent relationships (i.e., religiosity). Almost 90% of the respondents belong to some denomination: the majority are Roman Catholic (65%), followed by 20.2% Reformed, 2.7% Lutheran, 0.6% Greek Catholic, and 0.5% of other religions. Of them 11% are non-denominational. Regardless of whether or not they used to go to church, 80.4% consider themselves to be religious, 11% non-religious, 3% a staunch atheists, and 3.3% a seekers. Among the religious, the majority are those who consider themselves religious in their own way (48%), and 32.4% consider themselves religious in accordance with the teaching of the church.

Another important indicator of the quality of life is work and everything related to it. While 69% of the respondents work, 31% have no job. According to occupational status, every second respondent is an employee: 28.7% are in the private sector and 21.9% are in the public sector. In addition, 12.7% are entrepreneurs, 7.3% students, and 3.9% unemployed; 20% are retired; 1.8% are on maternity leave; 0.6% care for a

The Primary Results of the last Hungarian Identity Survey in Slovakia 39

sick family member; and 0.4% are homemakers. Of those who have a job, the majority work as subordinates (72%). The proportion of senior managers is 9%, middle mana gers 10%, and group leaders 9%.

How do they relate to their current jobs? Almost two thirds of respondents (64.2%) are satisfied with their current job, although part of them is also excited about other areas and new opportunities (39.7%), and there are those (24.5%) who feel that they have more to offer than they do in their current job positions. An additional 27.4% claim their job is also their hobby. On the other hand, almost 9% are unable to find a job, either because they cannot find any job (4.7%), or because they cannot find a job that matches their qualification and skills (4%).

The next indicator of the quality of life is financial situation. This time, we did not search for objective indicators (income, possession of material goods, etc.) – instead we were interested in the subjective assessment of their financial situation. When asked about the financial prospects of the family, almost three quarters of the respondents (73.2%) commented positively, still considering the financial situation of the family as good (32.7%) or encouraging (40.5%). Regarding the contrasting 17.2%, there are those who still perceive it as bad (15.2%) or alarming (2%). Almost 10% could not answer the question. Excluding these, 81% rate the family’s financial outlook as positive and 19% still find it bad or alarming.

The question of what vision one wanted to realize in the next five years was used to map out plans for the future. There were eight possible answers and more than one could have been chosen. Almost one in four respondents used this option, but the majority (76%) gave only one answer, that is they mainly focus on implementing one of the following plans: 15% want to buy a car and 14% an apartment, 10% want to find a better job, 5% want to start a family, 5% want to study/acquire a profession, 5% want to start a business, and 3% want to find a job. It is noteworthy, however, that most (19%) do not focus primarily on a plan for themselves, but want to act in the public’s interest in some way.

Returning to those who chose multiple responses (different combinations of twos, threes, and fours were circled), most (13%) associated their other plans with resolving the housing situation. Summarizing the combinations of plans for the future, the three most important are resolving the housing situation (in the case of 27% of respondents, this answer was indicated as a single or primary plan), acting in the public’s interest (25%), and buying a car (23%). The following are the additional plans in order of frequency: 15% want to start a family, 13% to find a better job, 12% to study/acquire a profession, 10% to find a job, and 8% to start a business.

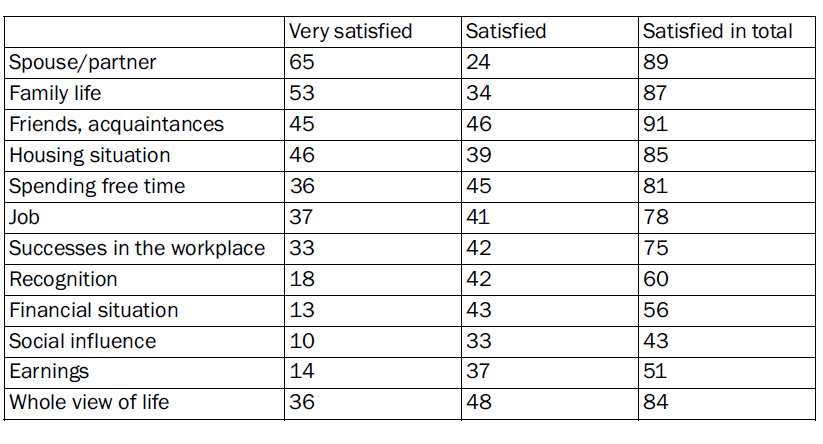

Satisfaction with different areas of life is also a reason and a consequence of the quality of life. We listed 12 areas and asked the respondents to rate them on a five-point scale indicating how satisfied they were with these areas in the previous year (i.e., in 2017). The results reveal several things (Table 1). Firstly, 84% of respondents are overall satisfied with their lives, of which 36% are very satisfied and 48% are satisfied. Furthermore, in 10 of the 12 areas assessed, the majority are satisfied (this means “very satisfied” and “satisfied”), ranging from 56 to 91%. Looking at overall satisfaction, they are most satisfied with their friends (91%), spouse/partner (89%), and family life (87%). On the other hand, if we only look at the areas they are very satisfied with, then the spouse/partner comes first (65%), followed by family life (53%), housing situation (46%), and friends, acquaintances (45%). The high level of job and housing satisfaction is in line with everything we have already learned from the answers to other questions: the majority consider their job a hobby or have at least a satisfying job, but there is a smaller group looking for a job or wanting a better job. The majority are sa tisfied with their housing situation, but there are those who regard the solution to their housing situation as their primary plan for the future.

Of the 12 areas listed, earnings are the area with which half of the respondents are satisfied (14% are very satisfied and 37% are satisfied), and the other half are dissatisfied. However, they are the least satisfied with their social influence (43% in total, of which 10% are very satisfied and 33% are satisfied). This means that, in addition to the areas already listed, the respondents are also more satisfied with their success in their workplace, the recognition they receive from others, and their financial situation and earnings than with their social influence. This is also interesting because, in gene ral, we find that people complain the most about their financial situation and earnings. In this case, however, they lack the impact on society the most.

Table 1: How satisfied were you with the following areas last year (i.e., in 2017)? The figures are percentages.

Regarding the next important area in life (i.e., settlement), it was found that 86% of respondents do not want to change it in the next stage of their lives. Rather, they want to live where they live now, mainly because they were born there (51%) and, moreover, because they feel good there (35%). This also reflects a high level of satisfaction,

The last question relating to the quality of life was, if they looked back on their life so far, how would they see it? The responses received again support the above-mentioned results: 89% are satisfied with their lives, of which 34% are fully satisfied and 55% are satisfied for the most part. Dissatisfaction is typical for 11% of respondents, of which 10% are rather dissatisfied and 1% are very dissatisfied with their lives.

3. Public interest

Respondents’ overall interest in political and public events was measured on a five-point scale. The following results were obtained. “Medium” interest is most common (33%); otherwise there are more people who are not interested in politics (46%) than those who are interested (21%).

Nevertheless, 74% still follow the development of public events in the country, even though 31% are not interested in politics. Although the remaining 43% are inte rested in politics, 37.7% do not want to be actively involved. However, in addition to mo nitoring public life in Slovakia, 5% would like to politicize themselves.

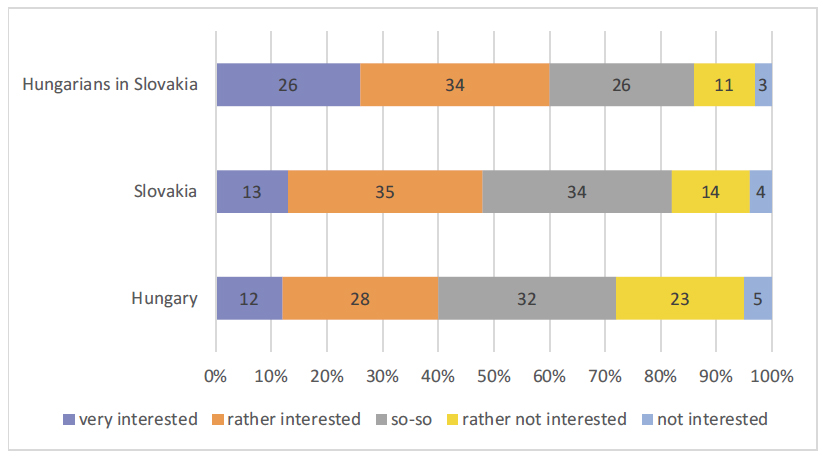

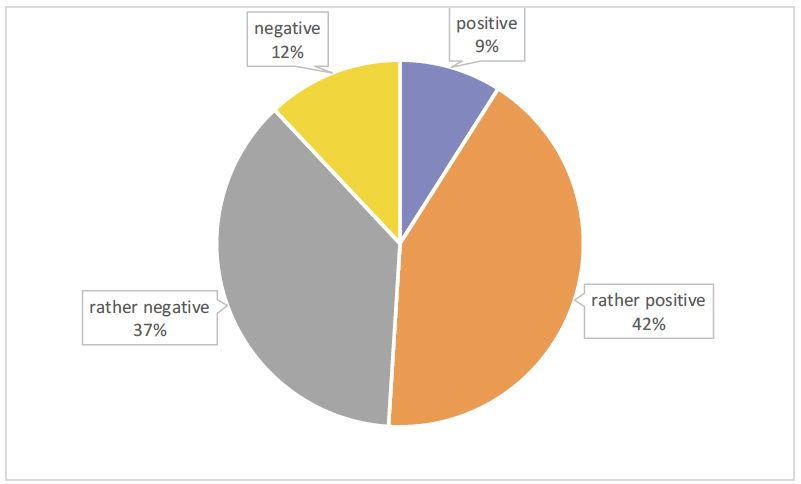

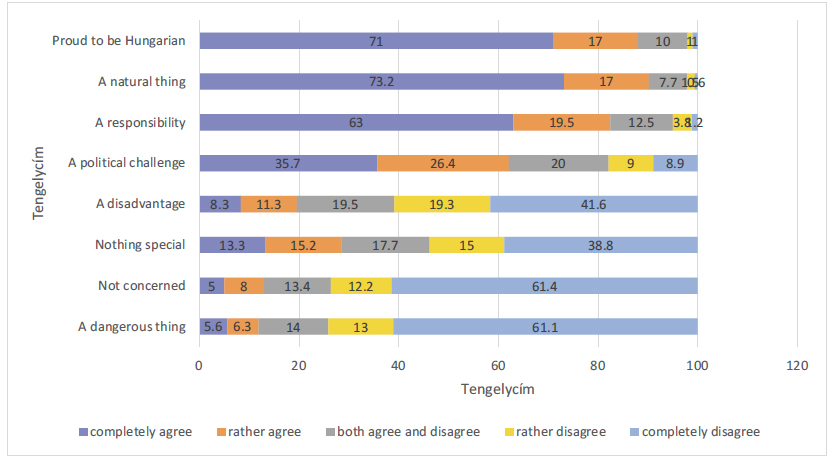

Among the specifically defined political events, such as the public issues related to the Hungarians in Slovakia, to Slovakia, and to Hungary, they are most interested in the situation of the Hungarians in Slovakia. Of the respondents, 26% are very interested in this topic, while only 13% and 12% are very interested in issues related to Slovakia and Hungary, respectively. Regarding the distribution of answers, 60% of respondents are very or fairly interested in the situation of the Hungarians in Slovakia, 48% in issues related to Slovakia, and 40% in issues related to Hungary. The lack of interest also varies: 14% of the respondents are not at all interested or rather not inte rested in the situation of the Hungarians in Slovakia, 18% in issues related to Slovakia, and 29% in issues related to Hungary (Figure 1). Respondents are most interested in the events that affect them or relate to their own situation the most, so we cannot talk about a complete lack of political interest but rather about its differentiation determined by the topic and the location.

Figure 1: To what extent are you interested in issues related to…?

However, regarding the interest in issues related to the European Union, not only is differentiation present, but two opposing camps emerge: 51% have a positive and a rather positive opinion, 49% have a negative and a rather negative opinion. (Figure 2)

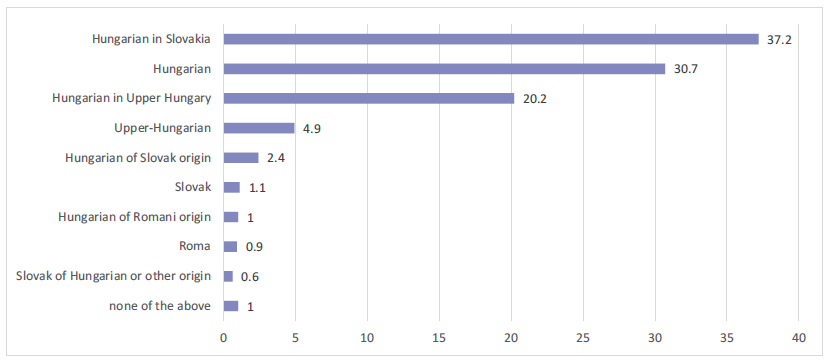

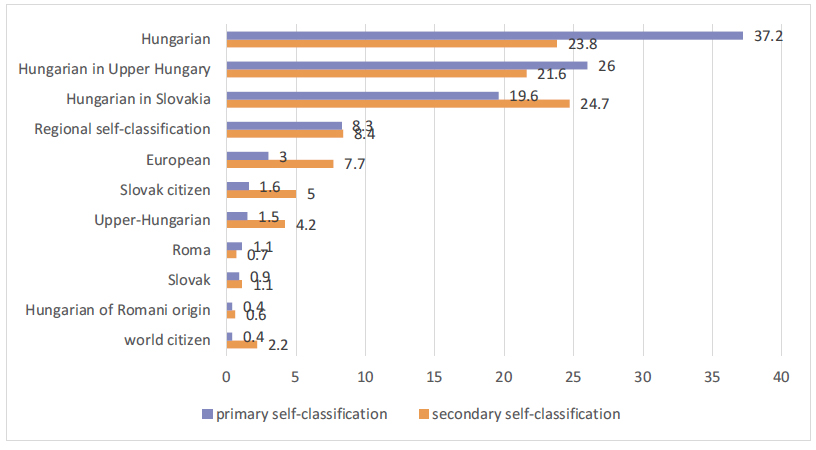

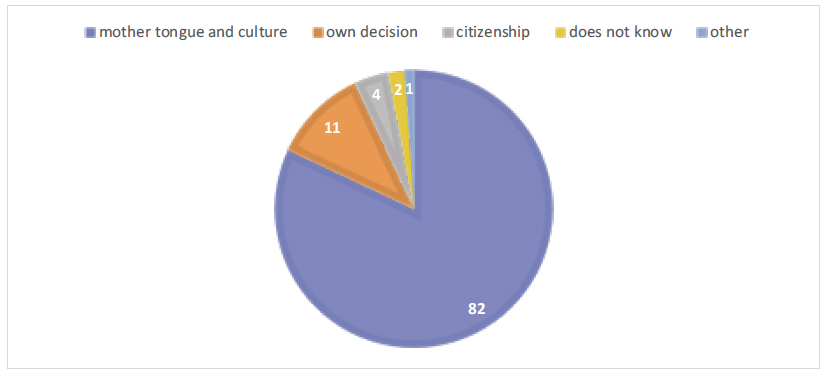

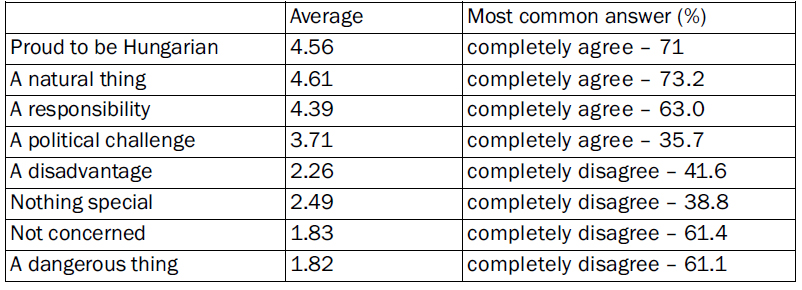

Figure 2: In general, what is your opinion about the European Union like?